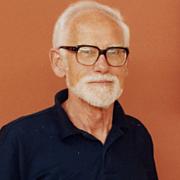

Michael H. Jameson, the Edward Clark Crossett Professor of Humanistic Studies, Emeritus, and a pioneering expert on Greek history, religion and epigraphy, died Aug. 18 in Stanford Hospital of cancer, after a brief illness. He was 79.

Michael H. Jameson, the Edward Clark Crossett Professor of Humanistic Studies, Emeritus, and a pioneering expert on Greek history, religion and epigraphy, died Aug. 18 in Stanford Hospital of cancer, after a brief illness. He was 79.

A professor of classics at Stanford since 1976, Jameson established an international reputation early in his career with his identification and publication of the Themistocles Decree in 1960. The inscription on the fifth-century B.C. stone tablet, which Jameson discovered in a coffee house in rural Greece, illuminated the history of the successful Athenian resistance to the Persians in 480 B.C. and has been called the most important document of the Persian Wars.

In addition to distinguishing himself as an epigrapher, Jameson was a path-finding figure in archaeology, said Marsh McCall, professor of classics. A specialist in Greek religion and economic history, Jameson interrelated archaeology with the social history and ecology of ancient Greece. Throughout his career, Jameson focused his study on a Greek peninsula, the Argolid, in the northeastern Peloponnese, where his work included initiating excavations in the ancient city of Halieis. He also directed a long-running and intensive field survey in the area, which brought together scholars from many disciplines to study patterns of human settlement and land development from 50,000 years ago to contemporary times.

“The genius of Mike Jameson was to combine work in three of the major classical sub-disciplines—ancient history, archaeology and epigraphy—and to be both a foremost international expert and a pioneer in all three,” said Paul Cartledge, a professor of classics at Cambridge University.

Jameson’s work “knitted together literary, epigraphical, ecological and archaeological evidence in a way in which an earlier generation of scholars had neither the impetus nor the skills to attempt,” said John Davies, professor emeritus in the School of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology at the University of Liverpool.

Jameson was born in London on Oct. 15, 1924, and grew up in England and Beijing, where his father was a professor of Western literature. In 1935, he moved with his mother to England.

After moving to the United States to attend college, Jameson earned a bachelor’s degree in Greek from the University of Chicago in 1942, when he was 17. Shortly before graduating, Jameson met his wife, Virginia, also a classicist, in a class on the Greek historian Thucydides. The first birthday gift he presented to his future wife was his translation of a play by Euripides, said his son, Anthony Jameson, a principal researcher at the German Research Institute for Artificial Intelligence in Saarbrücken. Michael Jameson served during World War II as a Japanese translator. He earned his Ph.D. from the University of Chicago in 1949.

Following postgraduate work at the American School of Classical Studies in Athens and at the Institute of Social Anthropology at Oxford, Jameson served as an assistant professor of classical languages and archaeology at the University of Missouri. He was a professor of classical studies at the University of Pennsylvania from 1954 to 1976. During that time he directed excavations at Halieis.

At Stanford, he continued to work in southern Greece by organizing an archeological and environmental survey of the southern Argolid in Greece with Tjeerd van Andel, professor emeritus of geology and human biology. The survey combined historical research on ancient, medieval and modern documents, and ethnographic and environmental studies.

Jameson was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Philosophical Society and the American Philological Association, of which he was president in 1981. He held visiting fellowships and professorships at the American School of Classical Studies, Athens; Christ Church College, Oxford; the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton; and the American Academy in Rome. Despite his long list of honors and publications, Jameson was “the opposite of the guy who shuts himself off in an ivory tower,” said his son Anthony. “He was constantly corresponding and visiting with colleagues from around the world, many of whom became close friends.”

Jameson’s research included the participation of numerous graduate and undergraduate students, many of whom remember him as a kind, generous teacher and an inspiring scholar who was totally absorbed in his work.

“Mike was a role model as a scholar. He was enormously informed, irreverent and always enthusiastic. He was always interested in the things around him,” recalled a former student, L. Vance Watrous, now a professor of art history at the University of Buffalo.

Once while driving in Greece, Jameson became so engrossed in describing the history of the use of slaves on farms in the surrounding countryside that he failed to notice a sign announcing that a bridge ahead had washed out, Watrous said. After his passengers began shouting in alarm, Jameson stopped, just meters short of a ravine.

Watrous learned to see fieldwork as part of an organic whole during visits with Jameson to local homes, where, over coffee and pastry, the professor would talk with villagers about their families and local events.

“Without knowing it, I gradually began to envision and carry out my own fieldwork as Mike was doing – that is, I did not see my archaeological work and my daily life in Greece as separate endeavors,” Watrous said, in a tribute he delivered at a celebration of Jameson’s 70th birthday. “Details of recent Greek history, the lives of the villagers and townspeople at every turn informed us and provided a perspective on the ancient problems and materials we were studying. … Above all, we came to appreciate our roles not as removed and objective ‘scientists,’ but as guests invited into a warm human community. I learned from Mike that it was people who mattered.”

In addition to his wife, Virginia Jameson of Palo Alto and son Anthony of Saarbrücken, Germany, Jameson is survived by sons Nick of Los Angeles, John of Tokyo and David of London.